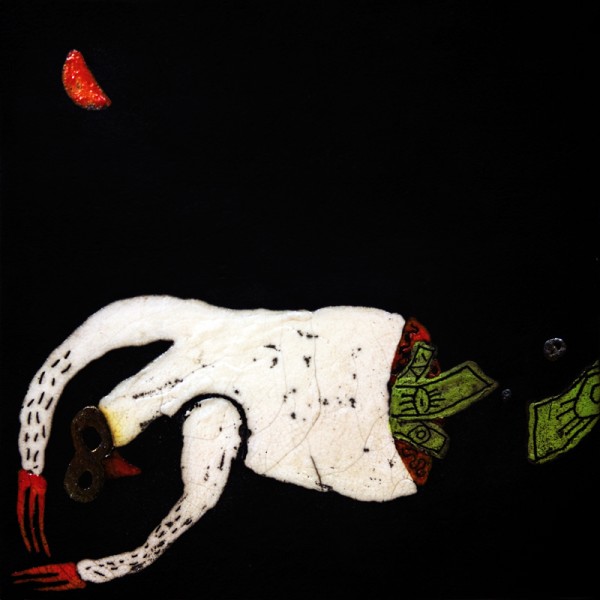

decollato

saldi di stagione

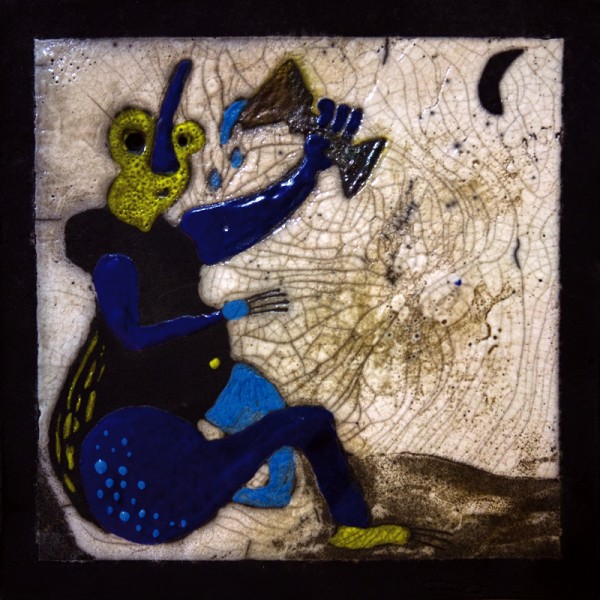

cyopekaf_fuoco_53

cyopekaf_fuoco_47

cyopekaf_fuoco_39

cyopekaf_fuoco_36

cyopekaf_fuoco_26

cyopekaf_fuoco_23

cyopekaf_fuoco_12

cyopekaf_fuoco_07

container

terracotta

guerre tiepide

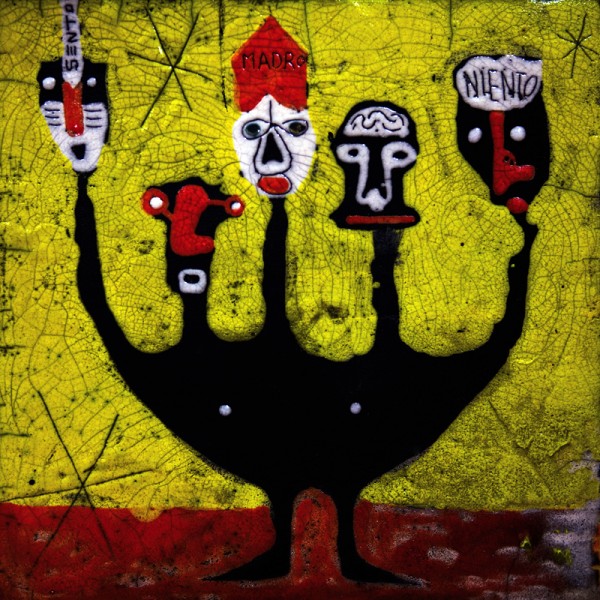

il popolo afono

everyday

selfdestruction (parte 1)

selfdestruction (parte 2)

romeo e giulietta

flebile

oro sodo

pre(carie)

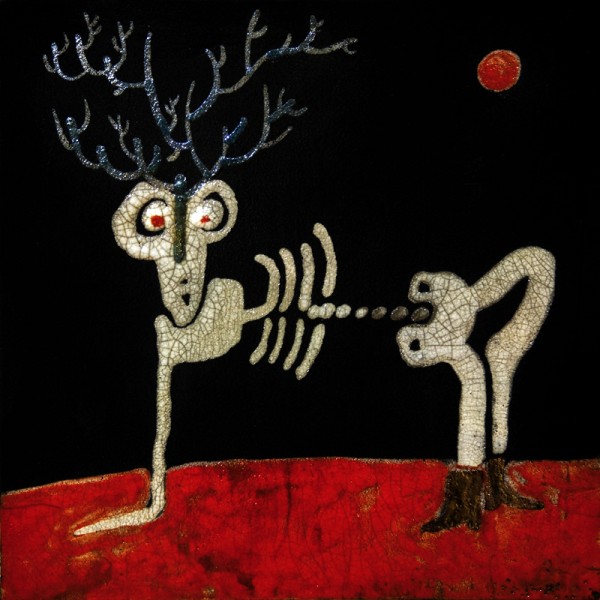

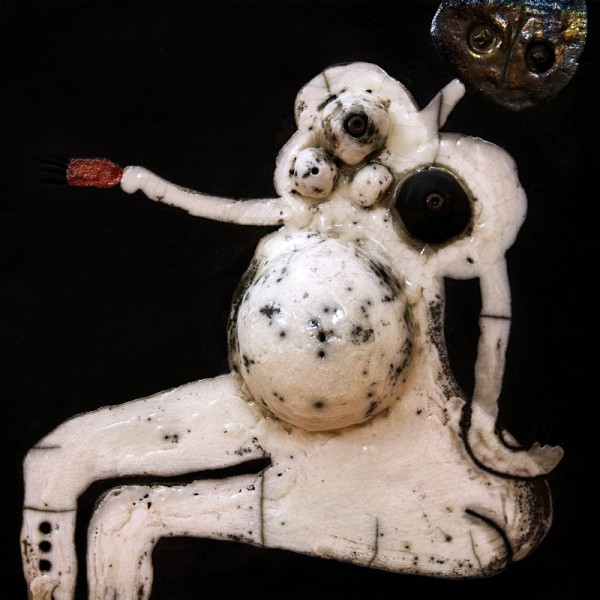

gravidanza sterile

suici(dio)

guerriero 2

guerriero 3

guerriero 1

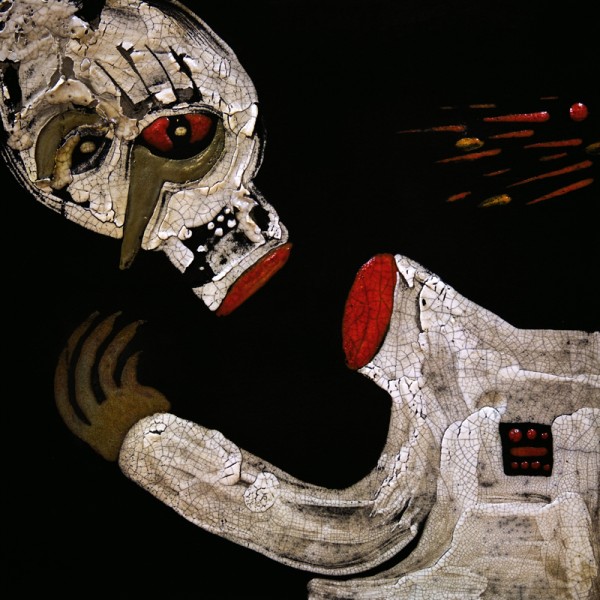

la peste

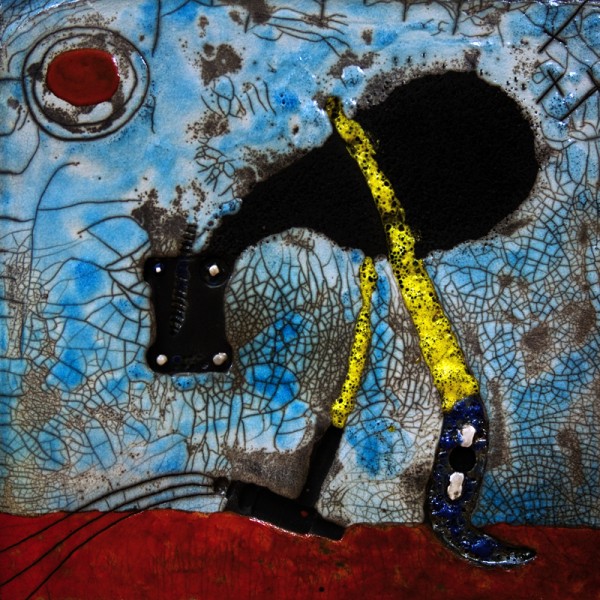

sole sciolto

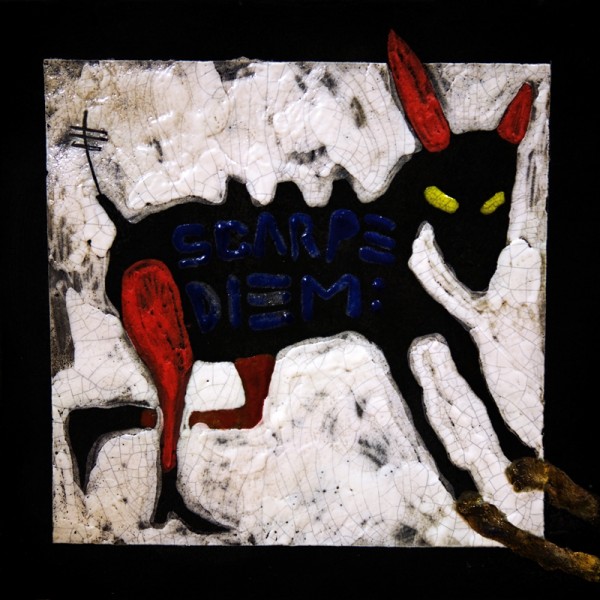

(s)carpe diem

sangue blu

r5

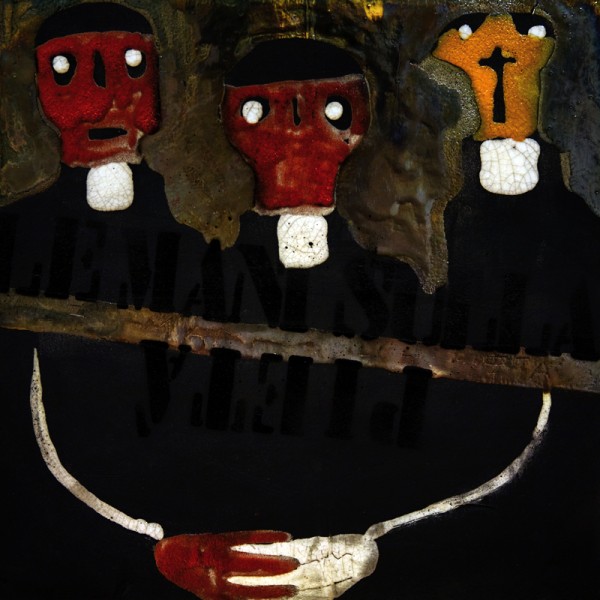

frati d'italia

verso il golgota (parte 2)

verso il golgota (parte 1)

la lingua

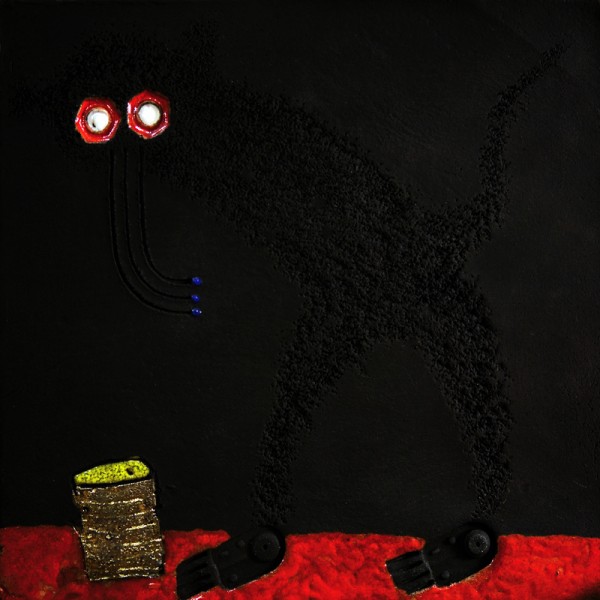

interno notte (parte 1)

interno notte (parte 2)

nuovo urbanesimo

dalla culla al barile

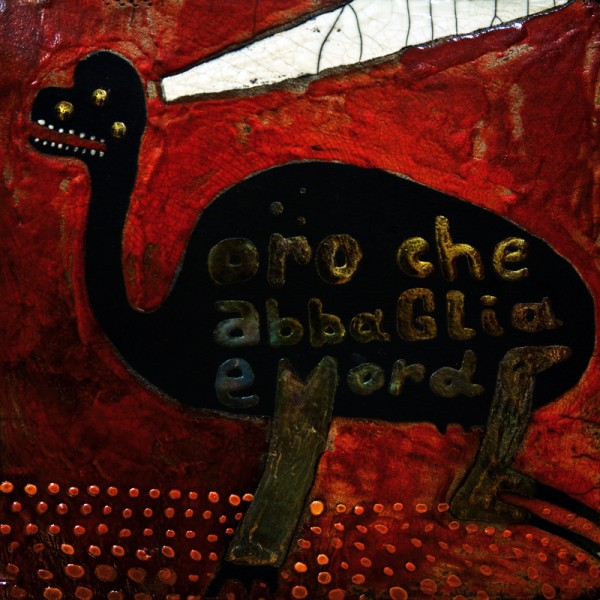

re mida (il contagio)

avodàfon

ferocia

in(digestione)

universale

next generation

libbbertà

omicidio, forse

misentropia

le mani sulla pietà

malacqua

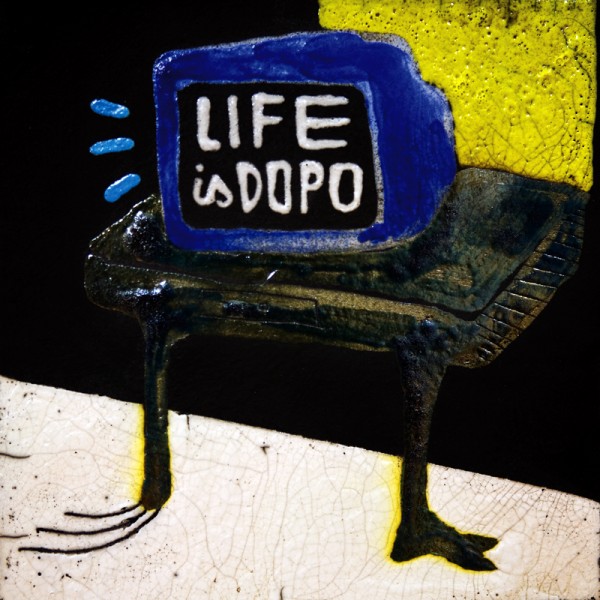

digitale terrestre

antennati

cover

fuoco @ overfoto / napoli

fuoco @ overfoto / napoli

fuoco @ overfoto / napoli

fuoco @ overfoto / napoli

The Cumana train that arrives at 9 a.m. at Montesanto throws up a excessive number of persons. How is possible that all these persons are contained in just two old wagons is a mystery. They are the inhabitants of those suburbs that start in the city and finish nobody knows. They work in offices, or shops, or they are very late students. The stationmaster, a mythological being half-woman half-tonsils, shouts to hurry up. The train that goes in the opposite sense is, obviously, half vacant. There are us and some other natives, for the rest there are African, Sri-Lanka, and Indian people. Everybody has that typical wooden rectangle, with a hole as handle, used to show their goods. Somebody uses a stroller, but the content is the same: sunglasses, bracelets, necklaces, toys, stuff that they sell, if police permits them, in the various local markets during the train path. Roberta, the special person who allowed us to realize the work you can see in this book, lives in the countryside between Cuma and Licola. Looking outside the train window – while the city fades away, houses become shorter, and the countryside has the upper hand over the city – we lose ourselves in our memories. Talking about the first times we saw Licola, the first thing is not the sea, but the whores…

It’s many hours that Shisha’s father doesn’t find his son. We know where he is, indeed, where they are. Because he’s not alone, he’s with Testa di chiodo (Nailhead), who’ll never admit it but he’s fallen in love with Azzurra, a Nigerian girl who prostitute herself on the Domitiana road. They fuck on the roadside, often standing, no matter if it’s hot or cold. One of us reaches them with a scooter, to warn them that Shisha’s father is very pissed off, and that it would be better for them to be at Cumana station in half an hour, with a good excuse. I go along with the father, in his car, to retrieve them. Nobody talks during the trip. «Dad, we were at Azzurra’s party, a friend of Daniele, sorry». I don’t move. Coming back there is still silence, but it’s just an overture to a oncoming domestic scolding. In the rear-view mirror I see the young ones chuckling.

…and the trains.

About 1 a.m. The train, the only one, sleepy, waits for us by the platform, under a humidity blanket that inch by inch penetrate our bones. Dogs approach barking and to avoid to wake up the station guardian (we don’t want to bother him, we don’t want to be shot), we pet them and we play a bit with them. It’s also to take time, to become familiar with the place, to understand if it’s all okay. We silently choose the part of the train we prefer, avoiding to cover the more recent drawings: a unwritten code is more valuable. The forefinger pushes on the spray cap, first without hesitation, then, a bit frozen, it hardens and you must blow on it, lick it if necessary. The skeleton of the work, the bones of the sense, the coloured replenishment: the pigments nebula suspends itself in mid-air, trapped by the hoarfrost drops, air is unbreathable. Sometimes we use a smog mask. Some cars cross the level crossing. Finished. Still unhappy we open the doors, jump in and, hell black in our hands, we write everywhere. Pure vandalism, rebels without a cause. Or a pause?

At Licola station, after forty minutes and three connections, there is the Cuma purification plant’s smell waiting for you (for more info read “Sangue Amaro”, published by L’ancora del Mediterraneo in 2010) and, after about a hundred meters further, there are the last Africa boys, the ones nobody picked up for a daily job. Building worker or farmer, more or less for them is the same, the salary is always miserable, but anyway, little by little, with it they can help their dear ones remained at the homeland. Meanwhile, they smile. Maybe too naïve, we wondered: they work their ass off: why the fuck they smile? An African boy explained it very well during an assembly organized after the Rosarno’s events: «It’s fear. Just fear», but also «They are scared to scare», he adds. «So much that at night I change street when I see a Italian. To avoid to scare him».

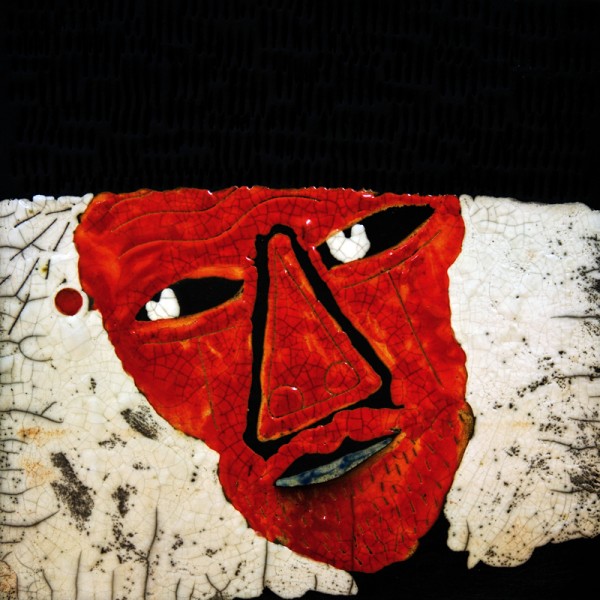

The road to Roberta’s house is a fast-flowing road, there is no sidewalk. It’s better to exit from the guardrail. Following the road to the sea, we walk by a open-pit sewer. We turn shortly before the Sibilla Cumana acropolis, nipping in the bud the questions we’d have liked to ask her. When in the alley the concrete has left space to the soil, the mud, the ditches, the road splits in two and there is a tree, a withered pomegranate where once there was a silent donkey tied to. Roberta always greets us smiling, offering tea and oranges. The lab is the kingdom of chaos. The several dogs of the house, accidentally waging their tails, contribute to break some ceramics she’s working on. It all started this way, out of curiosity. Can we come to visit you? We want to see what you do. Can we try to make a square? Can we… The appointment became monthly, then weekly: it became a regular thing. For almost three years. We become very fond not only of the work on ceramics, but also of the journey to the countryside, of the country’s time, of the near pinewood immersions, of the running to the sea. But we especially found in the fire the same loss of control we experience drawing in the streets for all these years. The unexpected that surprise you: at night the blue light scares you, somebody throws glass bottles from the balcony, somebody smiles and ask you why are you doing it. In this way, talking of flames, even if you can try to foresee the result, a burning colour always reacts in a different manner, a gust of wind or a grain of dust can change your plans. And so you try to get the best from the fate. But it’s the same in life, isn’t it? “We are acted”, Carmelo Bene would have said.

When it’s sunny, the lab goes open-air. Behind us, the land cultivated by Roberta’s grandfather, the hens shantytown, and a parrots aviary. A cat takes care of itself pointing a claw to the sky and the tongue to its genitals. Some days, when the wind is fair, the smell of purification plant goes away and so you really feel to be in the countryside, moreover a countryside beside the sea, surrounded by beauty. But it’s just a impression. Where you sow the wind and reap the whirlwind, the beauty can be just hell. (cyop&kaf)